CAVENDISH'S SECOND VOYAGE.

|

MISFORTUNES OF CAVENDISH BEGIN.

While England was not engaged in active war with Portugal, commerce with South American ports was in dispute, and the vessels of one nation became a legitimate prey of the stronger ones of others, so that we have the shameful spectacle of Spain, Portugal, and England preying indiscriminately upon one another, with no other motive than unlawful acquisition of wealth. Three days after the capture of the Portuguese vessel, Cavendish landed at a settlement called Placenzia, which they pillaged, and on the 16th surprised the town of Santos at a time when the inhabitants were nearly all at mass. It happened, however, through some mismanagement of the commander of the Roebuck, that the Indians obtained knowledge of the approach of the English in time to make way with a part of their possessions, principally through the first attack being made upon the houses instead of the church, where much of the wealth of the people was stored. The misfortunes of the expedition really began here, for the people having abandoned the place, Cavendish was unable to obtain a store of provisions which he stood very greatly in need of, and, wasting five weeks in a futile effort to replenish his ships, found himself in the beginning of winter, and only a little ways from Magellan Strait, with scarcely anything for his crews to subsist on.

CAVENDISH'S SAD STORY.

On the 23d of January, 1592, after having burnt St. Vincent, Cavendish put into Port Desire, which had been appointed as a rendezvous in case of a separation of the vessels. But on the 7th of February, the fleet was overtaken by a violent gale, and the following day the ships were so scattered that it was not until the 6th of March that the Roebuck and Desire reached the place appointed, and not until ten days afterwards that the Black pinnace put in her appearance. In the meantime the Dainty, which was a volunteer bark, having stored herself with sugar at Santos, put back to England. The sufferings which the crew now endured, by reason of the storm and lack of provisions, caused an uneasiness among the men, which came near breaking out into active mutiny. Their anger was chiefly directed against Cavendish, who, in order to secure his safety, left the Leicester, and took refuge on the Desire with Captain Davis. But he was little better off, for, according to his charges, Davis also turned against him, nor stopped short of open abuse and threatenings. He seems to have become the butt of every reproach and charge that could be preferred by any and all of his officers and men. An account is given of this most disastrous voyage, as drawn up by Cavendish himself in his last illness. It was addressed to Sir Tristram Gorges, whom the unfortunate navigator appointed his executor, and is one of the most affecting narratives that was ever written--a confession, wrung in bitterness of heart, from a high-spirited, proud, and headstrong man, who, having set his all upon a cast, and finding himself undone, endured the deeper mortification of believing he had been the dupe of those whom he implicitly trusted. Whatever may be our opinion of his culpability, we cannot withhold our sympathy, when we read the report of his extreme distress. He thus writes: "We had been almost four months between the coast of Brazil and the straits, being in distance not above 600 leagues, which is commonly run in twenty or thirty days; but such was the adverseness of our fortune, that in coming thither we spent the summer, and found the straits, in the beginning of a most extreme winter, not durable for Christians.

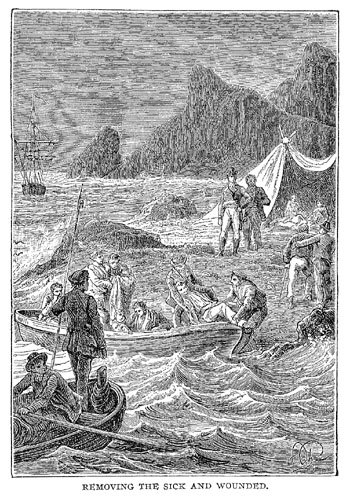

"After the month of May was come in, nothing but such flights of snow, and extremity of frosts, as in all my life I never saw any to be compared with them. This extremity caused the weak men (in my ship only) to decay; for, in seven or eight days in this extremity, there died forty men and sickened seventy, so that there were not fifteen men able to stand upon the hatches." Another relation of the voyage written by Mr. John Jane, a friend of Captain Davis, even deepens this picture of distress. The squadron, beating for above a week against the wind into the straits, and in all that time advancing only fifty leagues, now lay in a sheltered cove on the south side of the passage, and nearly opposite Cape Froward, where they remained till the 15th of May, a period of extreme suffering. "In this time," says Jane, "we endured extreme storms with perpetual snow, where many of our men died of cursed famine and miserable cold, not having wherewith to cover their bodies, nor to fill their bellies, but living by mussels, water, and weeds of the sea, with a small relief from the ship's stores of meal sometimes." Nor was this the worst, "All the sick men in the galleon were most uncharitably put on shore into the woods, in the snow, wind, and cold, when men of good health could scarcely endure it, where they ended their lives in the highest degree of misery."

ASTOUNDING STORIES TOLD BY A VOYAGER.

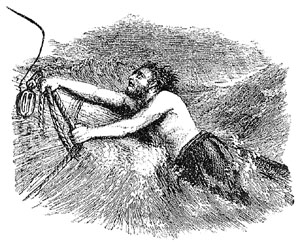

But the hardships precipitated by insufficient food, continuous storms and severely cold weather were increased by superstitious fears, which latter Cavendish does not mention, but which we find recorded in a book written by Purchas Pilgrim relating to "the admirable and strange adventures of Master Anthony Knyvet, who went with Master Cavendish in his second voyage," and was among the number forcibly put on shore and then abandoned. Knyvet's story, for marvels, if not for invention and imagination, rivals the adventures of Sinbad the Sailor. He wandered for a long while about Patagonia, and after gaining the coast of Brazil, was for many years among the "Cannibals." Many are the wonderful escapes from death which Knyvet is declared to have made. In the straits, pulling off his stockings one night, all his toes came with them; but this is not so bad as the fortune of one Harris, who, blowing his nose

|

CONCERNING THE BASE TREACHERY OF DAVIS.

Subsequently, it appears that confidence in Cavendish was partially restored, or else, having no further reliance in Davis, he considered himself more secure on his own vessel, and returned to the Leicester, and at length, on a petition signed by the whole company, he returned to the coast of Brazil for supplies, which, having been obtained, he made a second attempt to pass the Strait of Magellan. On the 15th of May they set sail again, but on the 20th, the Desire and Black pinnace were separated from the galleon, or admiral's ship. How this separation occurred we are not able to decide, but to the day of his death, Cavendish always maintained that Davis wilfully abandoned him to his fate. The friends of Davis, on the other hand, maintain that he proceeded to Port Desire, as instructed, and afterwards would have sought the Leicester, but for the violent opposition of his company who would not permit his departure, and that upon an effort to do so a mutiny arose, which was only quelled by acquiescence in their demands. The weight of evidence, however, goes far to establish the claim that Davis was ambitious to conduct an expedition of his own, and that to this end he designedly separated from Cavendish and continued on towards the straits.

|

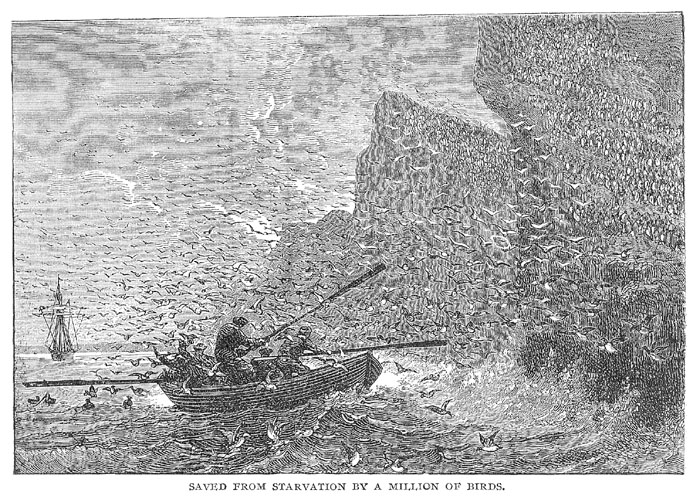

Being driven out to sea by a storm, he discovered and named the Falkland Islands, though history has denied to him the honor of this discovery, and has accorded it to Sir Richard Hawkins, who gave to them the name of Hawkins' Maiden Land, "for that it was discovered in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, my sovereign lady, and maiden queen." They have since been called Davis' Southern Islands, but in later years the first designation given them by Davis is maintained. After leaving Falkland Islands, the misfortunes which drove Davis there did not abate, for in steering westward again another storm arose of much greater severity, and which resulted in the loss of the pinnace, and a tearing away of all the sails and main-mast of the Desire. In addition to this disaster, the ships lost their course, and the sky being continually overcast Davis was unable to ascertain his position. In this extremity, therefore, he had recourse to prayer, in which he continued for a considerable time, believing that his end must soon come; but singular to relate, while thus engaged, Providence seemed to have interposed in his favor, for the sun burst through the clouds, and the wind almost immediately began to lull; at which Davis arose from his knees, and, first returning thanks to God, took an observation which showed that he was not a great distance from Magellan Strait, and taking new courage, he repaired his shattered sails, set up a new mast, and on the nth of October entered the mouth of the strait. But in reaching this harbor the crew was in a really pitiable condition, being long without proper nourishment, and exposed to a bitter cold, which so benumbed them that for sometime afterwards their flesh appeared to be dead and insensible to feeling. They found shelter in a cove for a few days, but provisions still being extremely scarce, they were compelled to continue their course, steering out again, intending to put back to Port Desire, if possible. After ten days' sailing on a stormy sea, they reached the desired haven, and on Penguin Island they found such an abundance of birds, that without difficulty they killed a number sufficient to supply them with meat in great abundance for more than a month thereafter, for like sorry fates had befallen many others on that crime-infested shore.

THE DOG-FACED MEN OF PATAGONIA.

Davis relates that one day while most of his men were absent on their several duties on shore, a multitude of the natives showed themselves, throwing dust upon their heads, "leaping and running like brute beasts, having vizors on their faces in resemblance of dogs, or else their faces were those of dogs themselves. We greatly feared lest they should set the ship on fire, for they would suddenly make fire, whereat we much marvelled. They came to windward of our ship, and set the bushes on fire, so that we were in a very stinking smoke; but as soon as they came within reach of our guns, we shot at them, and striking one of them in the thigh, they all presently fled, and we never saw them more." The reader of Cook's voyages will discover a passage relating to the New Guineans, describing the singular manner in which they produced a fire or smoke out of pieces of cane which they carried; in this particular very much resembling the reference which Davis makes to the sudden fire made by the natives about Port Desire. It was at this place also that nine of the seamen, whom Davis charged with having incited a mutiny, went on shore, and were never seen again. Whether they fell victims to the anger of the Indians, or were secretly murdered by orders of Davis himself, history has not been able to give particulars, as either supposition is a reasonable one.

A PLAGUE OF WORMS.

On the 22nd of December Davis sailed for Brazil with a store of 14,000 dried penguins, but in the beginning of February, in an attempt to obtain provisions at the Island of Placenzia, which is along the coast of Brazil, thirteen of his men were killed by Indians and Portuguese, and thus out of an original company of seventy, only twenty-seven were now left to man the Desire. From thence they steered for England, but were the sport of baffling winds, and made such slow progress that their store of fresh water ran short, and the weather being excessively warm, the dried penguins upon which they depended for subsistence began to corrupt, "and ugly loathesome worms of an inch long were bred in them." This plague is thus described by Mr. Purchas, the historian of the expedition: "This worm did so mightily increase, and devour our victuals, that there was in reason no hope 'how we should avoid famine, but be devoured by the wicked creatures. There was nothing that they did not devour, iron only excepted, our clothes, hats, boots, shirts, and stockings. And for the ship, they did eat the timbers; so that we greatly feared they would undo us by eating through the ship's side. Great was the care and diligence of our captain, master, and company, to consume these vermin; but the more we labored to kill them, the more they increased upon us; so that at last we could not sleep for them, for they would eat our flesh like mosquitoes." This plague of worms was not the only sore distress into which the crew fell, for most of them were now attacked by strange and horrible diseases that temporarily destroyed reason, so that more than one-half of the crew were at one time raving maniacs. This sorry condition was no doubt superinduced by the want of water, for heavy rain shortly afterwards falling gave them a temporary supply, and many speedily recovered. But eleven died between the coast of Brazil and Bear Haven in Ireland, so that only sixteen survived, and only five of these were able to work the ship into the home port.

CAVENDISH'S EXCORIATION OF DAVIS.

And now to return to Cavendish, whose opinion of Davis seems to have been substantiated by the verification of his prophecy; for as he declared would come to pass, Davis did return to Port Desire after a passage of the straits, and there provisioning himself in the manner described, set out upon a return to England, thus wilfully abandoning the Admiral with whom he had sailed. Thus in speaking of Davis and his conduct, Cavendish, in his letter already referred to, writes: "And now to come to that villain, that hath been the death of me and the decay of this whole action, I mean Davis, whose only treachery in running from me hath been utter ruin of all, if any good return by him, if ever you love me, make such friends, as he, least of all others, may reap least gain (a little confused). I assure myself you will be careful in all friendship of my last requests. My debts which be owing be not much; but I (most unfortunate villain!) was matched with the most abject-minded and mutinous company that ever was carried out of England by any man living. The short of all is this, Davis' only intention was utterly to overthrow me, which he hath well performed."

After the Desire and Black pinnace had separated from the fleet, as before described, the Leicester and Roebuck shaped their course for Brazil, but reaching thirty degrees south latitude they encountered a dreadful storm and were parted. Cavendish on the galleon made land at the Bay of St. Vincent, where he lay awaiting the Roebuck, having previously arranged to meet at a point thereabout in case of their separation for any cause. While lying in this bay a considerable party of Cavendish's men, in open defiance of his orders, went on shore to forage for provisions and incidentally to plunder the houses of the Portuguese farmers in the vicinity. While engaged in this freebooting enterprise, the Indians assembled in considerable force and cut the English off, killing twenty-four men and an officer and demolished the boat in which they had reached the shore; thus leaving Cavendish without either boat or pinnace. Shortly after, the Roebuck reached the bay in an almost dismantled condition, being destitute of masts and sails, and in despair of being able to rebuild her, Cavendish entertained an idea of sinking her, but on intimation of such intention he was violently opposed by the crews of both vessels, who, in the pressing emergency, were unwilling to part with even so sorry a hulk as the Roebuck now appeared to be, their ambition being to attack as speedily as possible some wandering vessel of the Portuguese, and in case of an engagement they correctly believed that the Roebuck might be as advantageous as though she were more seaworthy.

THE ENGLISH DEFEATED BY THE PORTUGUESE.

It was only a few days thereafter that the English had an opportunity of putting their valor to the test and carrying out their resolution, for, discovering three Portuguese ships in the harbor of Spirito Santo, they carefully planned an attack and at what they believed an auspicious time opened a broadside fire on the three surprised vessels. But they had not

|

Having refreshed himself and many of the wounded, despite the poor attention which they had received, recovering, Cavendish had a great desire to return to the straits, and used all his persuasive influence to induce his company to undertake the voyage, appealing to their cupidity, with assurances that they would be able to take valuable merchantmen after they had once passed the straits and reached the South Sea, while to return home in their beggarly and wretched condition must expose them to the taunts of all the English people. But all his arguments were of no avail, for not one of them would consent to continue the enterprise, being, to a man, resolved to hasten home as speedily as possible. Being thus opposed, Cavendish had recourse to stratagem, for, as he was the only one on the ship capable of directing her course, he gave his men to understand that he would not leave the island until his crew promised obedience to his orders; and the better to enforce his commands, he seized one of those who most strenuously opposed his wishes, and with his own hands adjusting a rope about his neck was resolved to act the part of an executioner; whereat others of the crew, perceiving their commander to be in no humor to be trifled with, promised that if he would release the unfortunate man, they would accompany him in any course that he resolved to take.

ANOTHER MASSACRE OF CAVENDISH'S MEN.

Directly afterwards Cavendish boldly avowed his intention of returning to the straits, but on the way landed at another island where he put his soldiers and carpenters to work building a new boat, while the sailors were set to the labor of mending and patching up the rigging and tackles of the ship. But so changeable had been the disposition of his men that Cavendish suspected treachery and betrayed the greatest anxiety that his crew should desert him on reaching land, or openly mutiny and force him back to England. Some of the wounded had not yet recovered, and these he left for a while longer on the 26 island, knowing that rest and attention there would result in their restoration much sooner than if compelled to submit to the hardships which they must undergo in a voyage through the straits. The island upon which they were stopping was scarcely more than a mile from the Brazilian mainland, where there was a considerable settlement of Portuguese who had been spectators of all the proceedings of the ship's company during the building of the boat. Shortly before wood and water were got on board, an Irishman, who was a member of the crew, having taken some deep affront at Cavendish, contrived to go over to the continent upon a raft and betray his defenceless comrades to the Portuguese. This was done in the night-time, and, besides those employed on the island and the sick, there chanced to be several men ashore who frequently stole away from the ship at night to enjoy the freedom of the land, not in the least suspecting any attack from the Portuguese, who up to this time, though unfriendly, had exhibited no hostile intention. But those who chanced to be on shore were attacked about two o'clock in the morning by a large party of Portuguese, and all were indiscriminately slaughtered. A sail which had been repaired lay on shore, and this the attacking party also seized, which added greatly to the serious loss sustained by the murder of his men; and thus the unfortunate Cavendish writes :

"I was forced to depart, fortune never ceasing to lay her greatest adversities upon me. And now I am grown so weak that I am scarce able to hold the pen in my hand; wherefore I must leave you to inquire of the rest of our most unhappy proceedings. But know this, that for the strait I could by no means get my company to keep their consent to go. In truth I desired nothing more than to attempt that course, rather desiring to die in going forward than basely in returning back again; but God would not suffer me to die so happy a man." These "unhappy proceedings" to which he refers may, so far as they are known, be very briefly noticed. An attempt was made to reach the island of St. Helena, for which the company had reluctantly consented to steer only on Cavendish solemnly declaring that to England he would never go; and that if they refused to take such course as he intended, the ship and all should sink in the sea together. This, as before related, made them more tractable; but having reached twenty degrees south latitude they refused to proceed any further, choosing rather to die where they were than to starve in searching for an island which they declared could never be found again. But the arguments and influence of Cavendish were not yet entirely exhausted, and finally he prevailed upon them to proceed southward again, and in dreadful weather he beat back to twenty-eight degrees south, and then stood for St. Helena, which was unfortunately missed, owing to contrary winds and the unskilfulness of the sailing master.

LETTER OF THE DYING ADMIRAL.

Having found himself a considerable distance from the island he made one more effort to induce his crew, which had now grown more mutinous, to proceed in quest of the island, alarming them with the scarcity of provisions; but with one voice they answered him that they would rather perish than not make for England. The rest of the record concerning this unfortunate expedition is fragmentary, since Cavendish died, as it is believed, of a broken heart before reaching England, and no satisfactory account could ever be gathered from those who had survived the expedition. His letter, from which we have quoted, was not closed when the galleon reached eight degrees north. From its commencement--and it must have been written at many different sittings--Cavendish had considered himself a dying man. It opens with great tenderness: "Most loving friend, there is nothing in this world that makes a truer trial of friendship than at death to show mindfulness of love and friendship, which now you shall make a perfect experience of; desiring you to hold my love as dear, dying poor, as if I had been most infinitely rich. The success of this most unfortunate action, the bitter torments whereof lie so heavy upon me, as with much pain am I able to write these few lines, much less make discourse to you of all the adverse haps that have befallen me in this voyage, the least whereof is my death." He adverts to the illness of "a most true friend, whom to name my heart bleeds," who, like himself, became the victim of the complicated distresses of this voyage. After the crowning misfortune of missing St. Helena, he says: "And now to tell you of my greatest ' grief, which was the sickness of my dear kinsman, John Locke, who by this time was grown in great weakness, by reason whereof he desired rather quietness and contentedness in our course, than such continual disquietness as never ceased me. And now by this time, what with grief for him and the continual trouble I endured among such hell-hounds, my spirits were clean spent wishing myself upon any desert place in the world, there to die, rather than thus basely return home again. Which course, I swear to you, I had put in execution had I found an island which the cardes (charts) make to be in eight degrees south of the line. I swear to you I sought it with all diligence, meaning there to have ended my most unfortunate life. But God suffered not such happiness to light upon me, for I could by no means find it; so as I was forced to go towards England, and having got eight degrees by the north of the line I lost my dearest cousin. And now consider whether a heart made of flesh be able to endure so many misfortunes, all falling upon me without intermission. And I thank my God that in ending me he hath pleased to rid me of all farther troubles and mishaps." The rest of the letter refers to his private concerns, and especially to the discharge of his debts and the arrangement of his affairs for this purpose, an act of friendship which he expected from the kindness of the gentlemen whom he addressed. It then takes an affecting farewell of life and of the friend for whom he cherished so warm an affection.

THE CHARACTER OF CAVENDISH.

In his two voyages Cavendish experienced the greatest extremes of fortune; his first adventure being both brilliant and successful while the last, chiefly through the bad discipline and evil dispositions of his company, was disastrous and unhappy. Cavendish was still very young when he died. No naval commander ever more certainly sunk under the disease to which so many brave men have fallen victims,--a broken heart. In many things his conduct discovered the rashness and impetuosity of youth, and the want of that temper and self-command which are among the first qualities of a naval chief. The reproach of cruelty, or at least of culpable indifference to the claims of humanity, which, from transactions in both voyages, and especially in the first, must rest upon his memory, ought in justice to be shared with the age in which he lived, and the state of moral feeling among the class to which he belonged by birth. By the aristocracy "the vulgar," "the common sort," were still regarded as creatures of a different and inferior species; while among the seamen the destruction of Spaniards and Portuguese was regarded as a positive virtue. By all classes, negroes, Indians and foreigners, were in no more esteem than brute animals,--human life as existing in beings so abject being regarded as of no value whatever. But if Cavendish was tinged with the faults of his class, he partook largely of its virtues,--high spirit, courage, and intrepidity. Those who might be led to judge of some points of his conduct with strictness, will be disposed to lenity by the recollections of his sufferings. As an English navigator his name is imperishable. On the authority of the accurate and veracious Stowe, we may in conclusion state, that Thomas Cavendish "was of a delicate wit and personage."

|