EXPEDITION OF SIR FRANCIS DRAKE.

|

Portugal and Spain, though ostensibly friendly governments, were nevertheless involved through rivalry, while England exhibited no small animosity over the apportionment made by the Pope of the new lands discovered, as already described, and her disregard of the papal bull and desire for acquisition of new territory at length led to open conflict with Spain, as will be presently described.

Queen Elizabeth had been for some time jealous of the power and riches acquired by Spain in the New World, but was anxious to avoid open conflict with her rival, and hoped to gain by adroitness what a more impulsive ruler would have attempted to obtain by open force. An opportunity presented itself when Sir Francis Drake made a tender of his services to the Queen, with a declaration of his purpose to make a voyage of discovery in the South Sea, even in violation of the assumed exclusive rights of Spain and Portugal under grants of donation by Pope Alexander VI.

THE INTREPIDITY OF DRAKE.

Drake was, of all men of his time, best qualified for the enterprise which he had proposed, combining as he did the intrepidity of his prototype of later years, Paul Jones, and with no less courteous instincts and unconquerable determination. Drake's proposition to enter the South Sea could not be publicly countenanced by Elizabeth, as such a course would have precipitated a conflict with

|

SECRECY OBSERVED BY DRAKE.

Drake wisely refrained from revealing his destination, for otherwise the Spanish government might enter protest, while the terrible sufferings of Haw-kin's crew, the death of Magellan, and more recent disasters, would make it difficult to secure seamen for such a voyage as he really intended. He accordingly publicly announced it as his purpose to make a voyage to Alexandria, and to give greater plausibility to his declaration, he fitted out a squadron of five vessels whose size was so small that they were hardly suitable for lake service. These, which were provided by Drake's friends, were as follows: The Pelican, of 100 tons, was the flag-ship of the squadron; The Elizabeth, a bark of 80 tons, Captain John Winter; The Swan, a bark of 50 tons, Captain John Chester; The Marigold, a bark of 30 tons, Captain John Thomas; and The Christopher, a pinnace of 15 tons, Captain Thomas Moone. On these vessels was a crew of 164 men.

Some surprise was expressed at the vast quantity of provisions and ammunition which was taken on board, and that the frame-work of four pinnaces, ready to be put together, should also be provided for such a short voyage. But against these suspicious precautions were the diminutive vessels, and a complement of men none too great to properly man them.

DANGERS IN THE SOUTH SEA.

The boldness required to undertake a passage of Magellan's Strait, even after it had been once successfully traversed, was probably greater than that originally exhibited, because of the disasters that had attended later attempts. De Solis had been murdered by the natives at the mouth of the La Plata while en-route for the strait. Magellan fell a victim to extraordinary courage, while De Lope who, from the top-mast of a ship in Magellan's fleet, first discovered the strait, met with a yet more terrible fate, in the opinion of all good Catholics, for he renounced his religion and became a Mohammedan. In addition to these disasters, nearly all of the commanders and the greater part of the crews that had sailed on the South Sea had either met death at the hands of natives or perished from disaster, hardship and anxieties which attended them on their voyage. These real and imaginary dangers were greatly increased by superstitions which represented the strait as having been closed by God to prevent further adventuring into the South Sea, where every horrible thing in man's imagination was believed to exist to destroy those making bold to sail its dangerous waters. But Drake, in addition to being an uncommonly bold man, whose spirit was most active in desperate undertakings, was all the more anxious to enter upon the exploration of the South Sea because of the dangers which were said to confront those sailing upon it. In addition to providing himself with a cargo of provisions which would likely last his crews for at least two years, he appreciated the value of shows and pageants, by which he hoped not only to impress the crews that accompanied him, but also the natives whom he would come in contact with. The furniture and equipage of his ships were therefore splendid, while the cooking utensils which he carried were generally of silver, and the tableware of gold or curious workmanship. Besides these, he took with him a band of musicians, appreciating the effect which music would produce upon the natives, and its exhilarating influence upon men when depressed by any anxieties. Thus while his fleet consisted of very small crafts, their equipment in large measure compensated for the otherwise sorry condition which they would have presented.

THE DEPARTURE ON A PIRATING CRUISE.

Having completed his arrangements Drake set sail from Plymouth on the I5th of November, 1577, but almost immediately encountering a gale he was compelled to put back to Falmouth to make some repairs to the Pelican and Marigold, both of which had received considerable injuries by being driven on shore. It was not until the 13th of the following month that they were able to

|

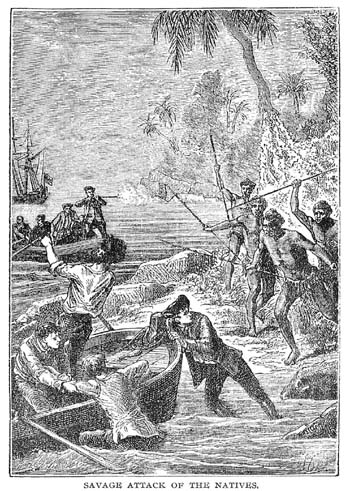

From Cape Blanco the squadron sailed to Mayo, where they fell in with a Portuguese ship bound to Brazil laden with wine, cloth and general merchandise. This vessel Drake also captured and gave the command to a Mr Thomas Doughty, another equally bold spirit, whose fate however was most deplorable as will be afterwards described. Only one other stop was made after the departure from Mayo until the fleet came in sight off a point of the Brazilian coast called Cape Joy. Here they put into harbor on the 5th of April, and on the morning following they discovered large fires on the shore around which were gathered a number of natives who were observed going through various incantations and the offering of sacrifices. These ceremonies, as was afterwards ascertained, were performed with the hope that their gods might avert the danger which the ships seemed to threaten. The natives had never before seen any ships and supposed them to be terrible monsters risen from the sea in the night for the purpose of devouring or otherwise destroying them. Before the day expired a violent storm, accompanied by vivid lightning and deafening thunder, on the other hand, led the superstitious sailors to believe that it was owing to the diabolical arts of the natives that the storm had been raised. On account of the fear thus entertained for each other the sailors had no intercourse with the natives, nor did the fleet remain long about Cape Joy though the climate was represented as mild and salubrious and the soil rich and fertile. Troops of wild deer of gigantic size were seen on this part of the

|

IN CONTACT WITH THE INDIANS.

On the 12th of May Drake entered a safe harbor at forty-seven degrees south, and the next morning put off in a boat to explore the bay. Directly after his departure a thick fog settled down which completely hid him from the vessels and for a considerable time there appeared great danger of his destruction. But by good fortune he managed to reach the shore where he discovered Indians, headed

|

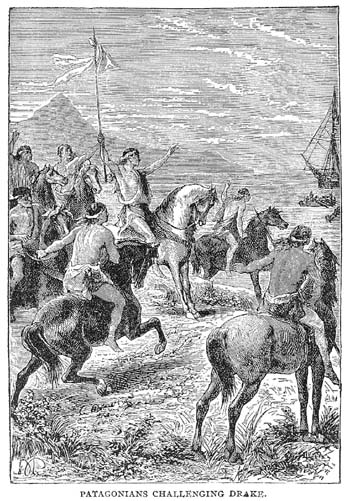

A BATTLE WITH THE PATAGONIANS.

On the 3d of June the fleet sailed out of the harbor, which has been named Seal Bay, and on the 12th they put into another bay, where they remained for two days, taking their stores from the prizes which they had made, and then sent the Portuguese vessel adrift. This anchorage was in the vicinity of Cape Horn, where after remaining for nearly three days they proceeded on to Port St. Julian where several of the crew going on shore they found the gibbet still standing upon which Magellan had executed some of the rebellious and mutinous members of his crew fifty years before On the following day the ships having been safely moored, Drake and some of his officers went off in a boat to examine the coast and on landing were met by two men of immense stature who gave them, by signs, a friendly welcome. These two were of the Patagonian tribes described by Magellan, and having been presented by Drake with a few trifles they set off, but directly returned again with several others of their people. The most hospitable feeling was constantly exhibited by the Patagonians, and very soon the natives and the members of the crew were on the most amicable terms. The English were armed principally with bows, a weapon which the Patagonian was also familiar with, and a trial of skill was made at which the Englishmen so far excelled that one of the Patagonians became jealous and with menacing gestures told the crew to leave the island. A Mr. Winter (not the captain of the Elizabeth), who accompanied the expedition, showed displeasure at this interruption, and partly in jest, but also to exhibit earnestness, he drew his bow with the intention of discharging an arrow to show the power of his weapon; but the strain was so great that the bowstring broke, and while he was in the act of repairing it, the natives discharged a shower of arrows, two of which wounded him severely, one in the shoulder, the other in the side. At this Mr. Oliver, who carried a gun, aimed his weapon at the attacking party but it missed fire, and he in turn was pierced through with an arrow, and fell mortally wounded. At this critical moment Drake ordered his men to protect themselves by means of the shields which they carried and to advance upon the Indians, at the same time to break every arrow that was discharged at them lest they might be recovered and used a second time. As the English advanced Drake seized a gun, and taking aim at the man who had killed Oliver, used it with such precision that he shot the native in the stomach, giving him a very painful wound and causing him to cry out in such agony that the rest of the natives taking alarm fled precipitately. Mr. Winter was borne off at once to the ships, but the body of Oliver was left until the following day when a

|

TRIAL AND EXECUTION OF CAPT. DOUGHTY.

This unfortunate affray, which appears rather the consequence of misunderstanding than design, was soon afterwards followed by a second even more deplorable incident. While the fleet lay in the Port of St. Julian, charges were brought against Captain John Doughty, who had been placed in command of the Portuguese prize, and he was brought to answer, before a court-martial, on a charge of conspiracy and mutiny. Specifically, the charge was that of conspiring to massacre Drake and his principal officers, and after thus enfeebling the expedition, to take possession of the ships, and enter either upon a voyage of discovery or piracy. The details of the charge and inquiry are both scanty and entirely insufficient to base an opinion respecting the guilt or innocence of Mr. Doughty. Accounts have appeared both apologetic and condemnatory of Drake, while others have sought to show that Mr. Doughty was a gentleman incapable of harboring such designs as had been charged against him. But whatever may have been the merit of his fate, Mr. Doughty was adjudged guilty by a jury of his countrymen, and condemned to death, leaving the manner of his execution within the discretion of the commandant. Drake very magnanimously permitted the condemned man to select either of three judgments : to be abandoned 011 the coast, taken back to England to answer the lords of the Queen's council, or to be executed on the island. Mr. Doughty choose the latter, only asking that he might before his death receive the holy communion with the captain-general, and that he might die the death of a gentleman. In accordance with these desires, Drake received the sacrament with the condemned man, and afterwards dined with him, the dinner being characterized by great sobriety, and at its conclusion they took their leaves by drinking to each other as if some great jollity was about to be begun. Being now prepared for his fate, Doughty walked forth with brave step, and a countenance which bespoke submission to his fate, and only requesting the bystanders to pray for him he submitted his neck to the executioner's axe. The body of Mr. Doughty was buried with those of Mr. Winter and of Mr. Oliver upon the island in the harbor, above which was erected a stone on which the chaplain cut the names of the unfortunate Englishmen and the date of their burial.

INCIDENTS IN THE PASSAGE OF THE STRAIT.

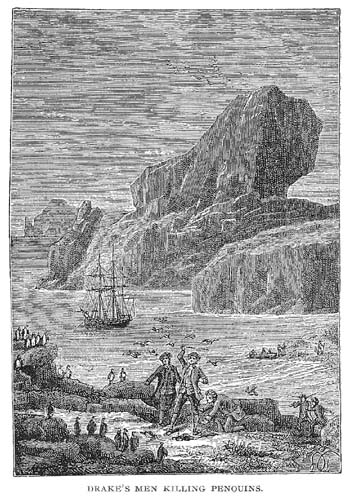

By the breaking up of the Portuguese prize, and the loss in the storm of two of the pinnaces the fleet was now reduced to three, and being supplied with wood and water and other necessaries they sailed from Port St. Julian on the 17th of August, and on the 20th they entered the Strait of Magellan, thus having passed around the greater portion of Terra del Fuego before discovering the

|

On the 6th of September Drake attained the long desired happiness of entering the South Sea, fortune having favored him incessantly from the time he left Falmouth and which had enabled him to make a passage of the strait in less than a fourth of the time required for Magellan to traverse it.

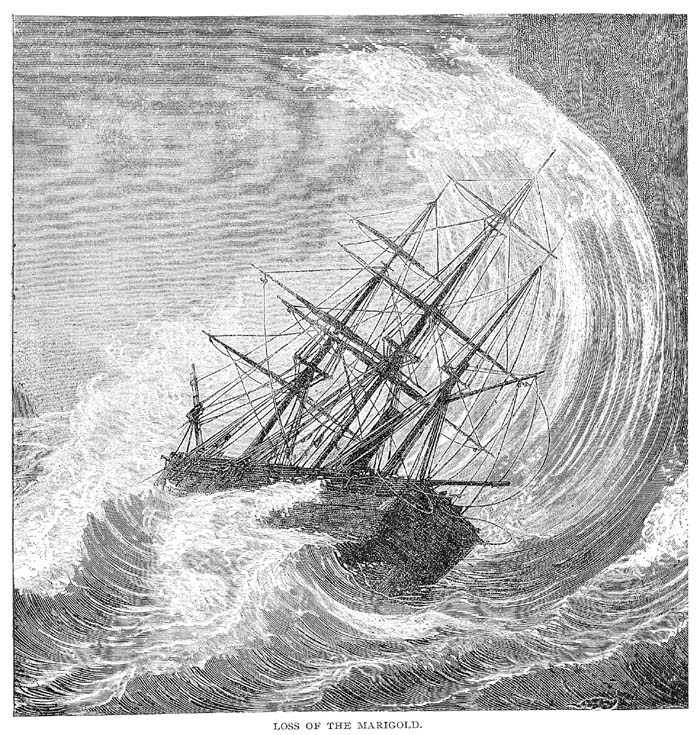

DRIVEN OUT TO SEA AND LOSS OF THE MARIGOLD.

After entering the ocean he directed his fleet in a north-west course, where, having proceeded 70 leagues, he was overtaken by a violent and steady gale, which drove his vessels over 200 leagues to the west of the Strait. On the 24th the weather moderated, and the wind shifting they were enabled to partly retrace their course, and after seven days standing to the north-east, they discovered

|

A MASSACRE, AND HORRIBLE SUFFERINGS OF THE SURVIVORS.

Drake in the meantime was carried back to 55 degrees south, and expediency admonished him to run in among the islands along the coast of Terra del Fuego, where he remained during the severe season and replenished his provisions by the capture of a large number of seals. Here a pinnace was set up and made ready for sea; but another violent gale coming on, she was driven into the

|

|