FIRST CONFLICT WITH THE SANDWICH ISLANDERS.

|

The attack was not followed up, however, but the feeling of uneasiness continued to increase. The next morning the cutter belonging to the Resolution was missed, having been stolen during the night, and to recover this Cook armed nine of his marines, and taking a musket himself, went ashore in the pinnace, first giving orders to capture every canoe possible, and to seize upon and hold as hostages any priests or chiefs that might be arrested. The events which followed are thus described by Captain King, who succeeded to the command of the Resolution after Cook's death:

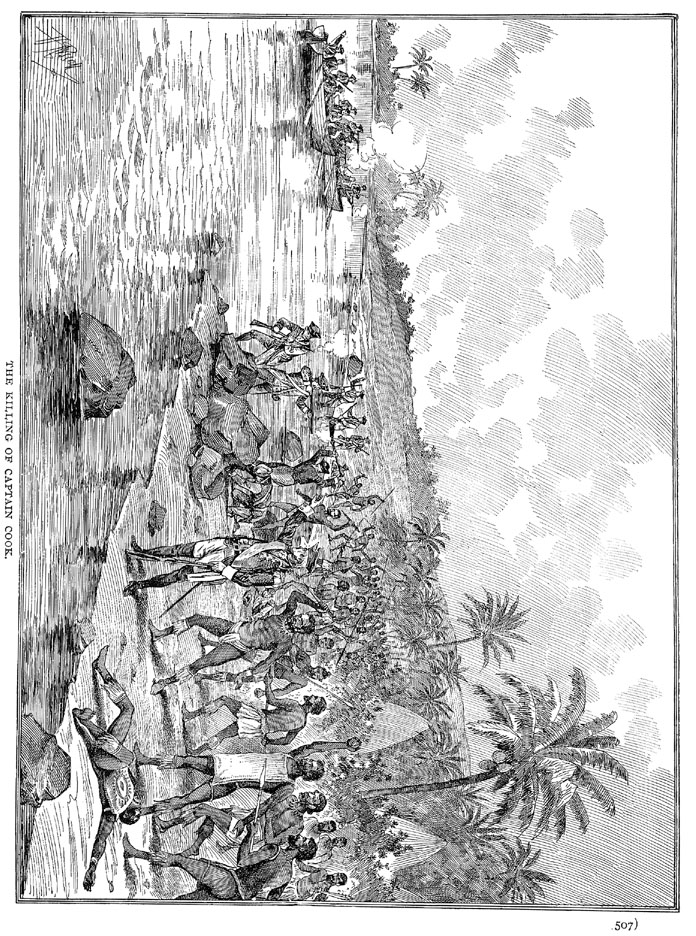

THE KILLING OF CAPTAIN COOK.

"In the meantime, Captain Cook having called off the launch, which was stationed at the north point of the bay, and taken it along with him, he proceeded to Kowrowa and landed with the lieutenant and nine marines. He immediately marched into the village, where he was received with the usual marks of respect: the people prostrating themselves before him, and bringing their accustomed offerings of small hogs. Finding that there was no suspicion of his design, his next step was to inquire for Terreeoboo and the two boys, his sons, who had been his constant guests on board the Resolution. In a short time the boys returned along with the natives who had been sent in search of them, and immediately led Captain Cook to the house where the King had slept. They found the old man just awoke from sleep, and after a short conversation about the loss of the cutter, from which Captain Cook was convinced that he was in no wise privy to it, he invited him to return in the boat, and spend the day on board the Resolution. To this proposal the King readily consented, and immediately got up to accompany him.

"Things were in this prosperous train, the two boys being already in the pinnace, and the rest of the party having advanced near the water-side, when an elderly woman called Kaneekabareea, the mother of the boys, and one of the King's favorite wives, came after him, and, with many tears and entreaties, besought him not to go on board. At the same time, two chiefs who came along with her laid hold of him, and insisting that he should go no farther, forced him to sit down. The natives who were collecting in prodigious numbers along the shore, and had probably been alarmed by the firing of the great guns and the appearances of hostility in the bay, began to throng round Captain Cook and their King. In this situation, the lieutenant of marines observing that his men were huddled together in the crowd, and thus incapable of using their arms, if any occasion should require it, proposed to the captain to draw them up along the rocks close to the water's edge; and the crowd readily making way for them to pass, they were drawn up in a line at the distance of about thirty yards from the place where the King was sitting. All this time the old King remained on the ground, with the strongest marks of terror and dejection in his countenance; Captain Cook, not willing to abandon the object for which he had come on shore, continued to urge him in the most pressing manner to proceed; whilst, on the other hand, whenever the King appeared inclined to follow him, the chiefs who stood round him interposed at first with prayers and entreaties, but afterward, having recourse to force and violence, insisted on his staying where he was. Captain Cook therefore, finding that the alarm had spread too generally, and that it was in vain to think any longer of getting him off without bloodshed, at last gave up the point; observing to Mr. Phillips that it would be impossible to compel him to go on board, without the risk of killing a great number of the inhabitants.

"Though the enterprise which had carried Captain Cook on shore had now failed, and was abandoned, yet his person did not appear to be in the least danger till an accident happened, which gave a fatal turn to the affair. The boats which had been stationed across the bay, having fired at some canoes that were attempting to get out, unfortunately had killed a chief of the first rank. The

|

"Four of the marines were cut off amongst the rocks in their retreat, and fell a sacrifice to the fury of the enemy; three more were dangerously wounded, and the lieutenant, who had received a stab between the shoulders with a pahooa, having fortunately reserved his fire, shot the man who had wounded him just as he was going to repeat his blow. Our unfortunate commander, the last time he was seen distinctly, was standing at the water's edge, and calling out to the boats to cease firing, and to pull in. If it be true, as some of those who were present have imagined, that the marines and boatmen had fired without his orders, and that he was desirous of preventing any further bloodshed, it is not improbable that his humanity, on this occasion, proved fatal to him; for it was remarked, that whilst he faced the natives, none of them had offered him any violence, but that having turned about to give his orders to the boats, he was stabbed in the back, and fell with his face in the water. On seeing him fall, the islanders set up a great shout, and his body was immediately dragged on shore and surrounded by the enemy, who, snatching the daggers out of each other's hands, showed a savage eagerness to have a share in his destruction."

The marines having been killed or beaten off, the body of Captain Cook fell into the hands of the natives, who at once cut it up, and, after offering it great indignities, burnt a considerable part. On the night following, two friendly islanders came out to the ship, bearing with them about nine pounds weight of flesh, that proved to have been a part of the body, and which they had brought to

|

Unfortunately these overtures for peace were not understood until several more of the natives had been sacrificed to the vengeful disposition of the marines, so that the shore was almost lined with dead bodies, while smoke from a hundred burning huts told how great had been the havoc.

SURRENDER OF PARTS OF CAPTAIN COOK'S BODY.

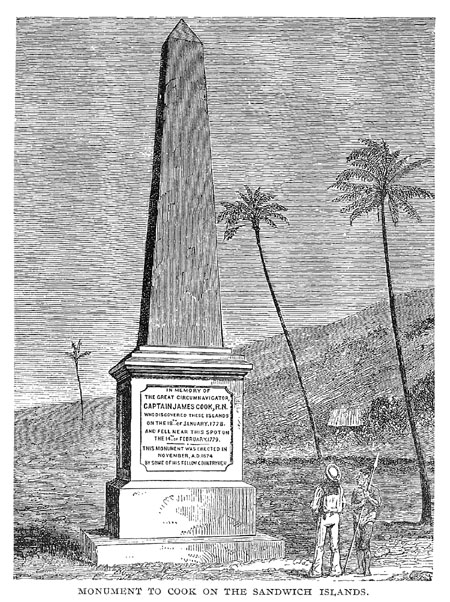

In compliance with requests of Captains King and Clerke, a great number of people came down from the hill, carrying pieces of sugar-cane, bread-fruit, and plantains, who were preceded by two drummers. As they reached the sea-shore they sat down, and a chief, named Eappo, motioned for a boat to be sent to them from the ship. In response to the signal, Captain Clerke went himself on shore with a party of his marines, whereupon Eappo entered the boat, and delivered to Captain Clerke a package covered with fine new cloth and a cloak of black and white feathers, indicating that therein were the mortuary relics of Captain Cook. And so it proved to be, for on opening the bundle there were found entire both hands of the lamented commander, which were readily recognized by a scar of an old wound; there was also a portion of the skull, to which the scalp and two ears were still attached, and the bones of both arms from which the flesh had been cut. Says Captain King: "Eappo, and the King's son, came on board, and brought with them the remaining bones of Captain Cook, the barrels of his gun, his shoes, and some other trifles that belonged to him. Eappo took great pains to convince us that Terreeoboo, Maiha-maiha, and himself, were most heartily desirous of peace; that they had given us the most convincing proof of it in their power; and that they had been prevented from giving it sooner by the other chiefs, many of whom were Still our enemies. He lamented, with the greatest sorrow, the death of six chiefs we had killed, some of whom, he said, were amongst our best friends. The cutter, he told us was taken away by Pareea's people, very probably in revenge for the blow that had been given him, and that it had been broken up the next day. The arms of the marines, which we had also demanded, he assured us, had been carried off by the common people, and were irrecoverable; the bones of the chief alone having been preserved, as belonging to Terreeoboo and the Erees gods. Nothing now remained but to perform the last offices to our great and unfortunate commander. Eappo was dismissed with orders to taboo all the bay; and, in the afternoon, the bones having been put into a coffin, and the service read over them, they were committed to the deep with the usual military honors. What our feelings were on this occasion, I leave the world to conceive; those who were present know that it is not in my power to express them."

EXTRAORDINARY VENERATION OF CAPTAIN COOK'S BONES.

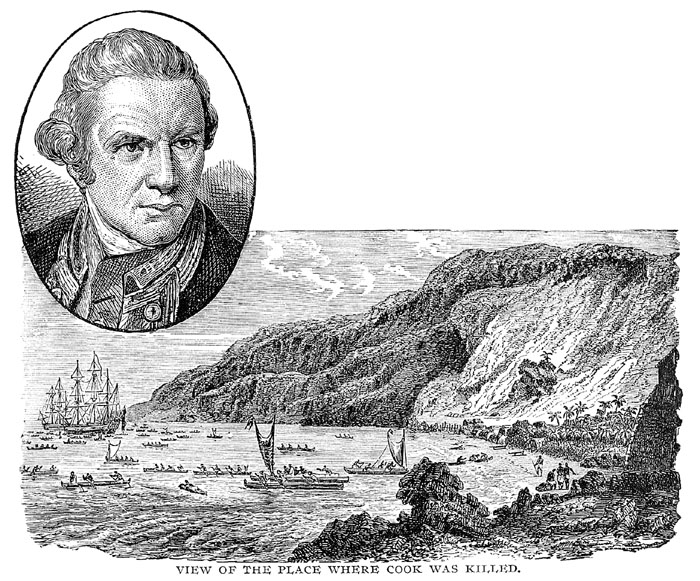

The account given by Captain King of the killing of Captain Cook and the indignities offered to his remains, does not agree with information since given by the natives to missionaries stationed on the islands. Mr. Ledyard, who was one of the marines who accompanied the expedition, also dissents from Captain King's opinion, and declares that the murder of his commander was not premeditated, but was precipitated by the rash act of one of the marines killing a chief, and a series of petty quarrels and abuses, for which the ships' crews were responsible. The mutilation of Captain Cook's body was at first considered as a proof of disgusting revenge, but it was in fact only an evidence of the high honor in which he had been held. Mr. Ellis, who took great pains to ascertain all the facts attending this melancholy occurrence, was informed by one of the natives, who was present at the time, that after Cook's death "they all wailed. His bones were separated, the flesh was scraped off and burnt, as was the practice in regard to their own chiefs when they died. They thought he was the god Rono, worshipped him as such, and after his death, reverenced his bones."

It has already been mentioned that the extraordinary honors paid to Captain Cook at the Sandwich Islands, were rendered in the belief that he was their god Rono or Orono. "But," says Mr. Ellis, "when in the attack made upon him, they saw his blood running

|

DEATH OF CAPTAIN CLERKE.

On March 15, 1779 the two ships, Resolution and Discovery, took their departure from the Sandwich Islands, and steered northward again in quest of the long sought passage around North America. Captain Clerke, though suffering in the last stages of consumption, was unwilling to abandon the first purpose of the voyage, and being now invested with the command of the expedition, his ambition made him the more anxious to succeed in the great undertaking, and this intense desire no doubt served to prolong his life, as it nerved him to increased endeavor.

The two ships made excellent progress, and in a month the shore of Kamtchatka was reached, where a considerable stay was made to increase their store of provisions by traffic with the Kamtchadales. Thence continuing, the vessels pushed northward to 80 degrees (to Icy Cape), but finding another barrier of ice, they sailed south and then north-west to a like latitude along the shore of Siberia. The extreme limit was named North Cape, from which, on account of the impassable ice, the expedition returned southward again. On August 22d when the ships were near the harbor of St. Peter and St. Paul, on the coast of Kamtchatka, Captain Clerke expired, being no longer sustained or inspired by an ambition; for his hopes were destroyed by the limitless fields of ice that disputed his further passage northward. In the harbor was a small Russian village and garrison, and to this place the remains were taken and given Christian burial, a priest officiating at the service, and the soldiers of the garrison and all the marines firing a volley over his grave, which was made under the shadow of a large tree that stood on the north side of the harbor.

Captain Clerke had accompanied Captain Cook on his three voyages, on the first acting as master's mate, on the second as lieutenant, and on the third being promoted to the command of the Discovery, and after Captain Cook's death he became commander-in-chief of the expedition. At his death, Captain Gore succeeded to the command of the Discovery, and Captain King was made chief com-commander. After this change, considerable time was spent on the shore at Kamtchatka among the people of that frigid clime, hunting bears, wolverines, foxes, wolves and seals, by which a large quantity of fresh meat was obtained, and many valuable furs. The vessels then departed, calling at points in Japan, China, and the East India Islands, so that it was not until the 4th of October, 1780, that the expedition returned to England, having been absent for a period of four years, two months and twenty days.

|